Ways to Create Psychologically Safe Workplaces

"Maybe I should kill myself," my intern told me one day in response to my question about her plans for the future. As a manager, this was certainly not the first time that I had first-handly encountered casual remarks that alluded to mental health challenges in the workplace. Yet, many of these concerns were usually brushed off by fellow colleagues as "part and parcel of life" or presented as an opportunity for them to preach about "finding the silver lining in everything". Talk about toxic positivity.

I have worked in the hospitality industry for close to 5 years now. Having worked my way up from a part-timer figuring out my career path fresh out of high school to a mid-level manager juggling multiple responsibilities, I have had my fair share of emotional breakdowns and struggles with interpersonal relationships and communication skills both up and down the food chain. At the same time, I have also witnessed many colleagues struggle with their own thoughts, some confessing that they had been secretly crying in the bathroom during lunch and others who silently resign and disappear from the group chats and social circles, never to be heard from again. When this happens, I often wish that I could do more to help.

This led me to a classroom at The Singapore Red Cross Centre for Psychosocial Support. Developed by the World Health Organisation and the Singapore Red Cross, Psychological First Aid (PFA) is a beginner-level course that equips learners with essential skills to support individuals experiencing emotional distress. It provides a solid foundation in mental health awareness, stress management, and self-care, along with guided practice in applying the core Psychological First Aid framework. There are no prerequisites to attend this course, and a background in psychology is not required. It is perfect for anyone who wants to learn more about how to respond to loved ones or strangers experiencing strong emotional distress.

Over the course of two years (I got certified in basic psychological first aid (PFA) in 2024 and advanced psychological first aid (APFA) in 2025), I learnt how to triage and respond to emotional distress confidently in an empathetic manner using the Look-Listen-Link model. In short, PFA aims to comfort rather than offer solutions for those struggling, and it is not meant as a replacement for therapy or counselling.

For the Basic PFA course, my trainer spent a day going through the basics of self-care, the importance of psychosocial support and a simple structure of how to conduct psychological first aid to strangers or friends in need. It also included role-play activities with fellow participants so we could practice our skills and obtain real-time feedback from a trained counsellor.

The Advanced PFA course covers more complex emotional reactions and concludes with an assessment, which trainees are required to pass before obtaining the certification. Over the course of two days, we learnt how to respond to individuals presenting complex emotional reactions such as self-harm, suicide, flashbacks and aggression. This course was taught by psychologists and trainers through theory, sharing sessions and role-play activities. Participating in this course made me realise how important it is to have trained PFA providers in every workplace, regardless of industry or demographics, as anyone can display any complex emotional reaction at any point in time. My fellow trainees ranged from millennials to middle-aged working professionals in a wide array of industries, from education to food manufacturing. Despite our differences in age and professional background, all of us had experienced encounters with complex emotional reactions in our workspaces and wanted to learn how to respond more effectively and humanistically.

PFA Model from Lifelines https://www.lifelines.scot/post-trauma-support-providing-psychological-first-aid

When my intern expressed her desire to end it all, my heart sank. But I didn’t flinch. Instead, I remained calm and encouraged her to share her true feelings. Once I assessed that she was not actively suicidal, I gently redirected the conversation to exploring different career options in relation to her strengths and interests and shared resources on where and how to access professional support. Fast forward a few months later, she has now taken on a full-time position in the role that she has decided on and is utilising her creative skills to bring a smile to others.

According to Harvard Business Review, it is estimated that the average person spends one-third of their lives, or equivalent to 90,000 hours at work. In other words, if we are spending most of our time at work, we deserve to be in workspaces that are psychologically safe and inclusive. And this responsibility does not have to fall solely on each organisation’s Human Resources team or upper management.

We can start by establishing buddy systems among same-level employees within each team. Buddies can pair up and support each other in managing workloads, company culture and daily tasks. They can also support each other and foster a sense of belonging within the team. This buddy system can then be elevated to regular check-ins by assigned managers, who can provide technical support (with work-related struggles) and emotional support (with personal grievances in relation to work).

Next, we can make mental health resources more readily available. This can include website links, brochures or workplace sharing sessions on various topics so that employees are aware of where to access support. For instance, sharing sessions for working mothers can be organised to disseminate information on government-subsidised child care, counsellors who specialise in postpartum depression and helplines such as Mindline that are always available in times of distress. Small support groups can be formed within identified groups to foster a sense of community and knowledge-sharing practices. These may alleviate the stress of working mothers who shoulder a lot of responsibility in caring for children and sustaining an income for the family.

Most organisations already provide basic orientation and onboarding for new hires and leadership training for emerging team leaders. Perhaps these trainings could be expanded to include topics such as “gentle communication skills”, which demonstrates how to use non-accusatory language when giving feedback and how to practise active listening. It could be helpful to encourage and guide employees on how to properly establish and respect individual boundaries and cultural differences at work, too. By making small changes to daily interactions among colleagues, employees would feel more comfortable to share their ideas and be themselves.

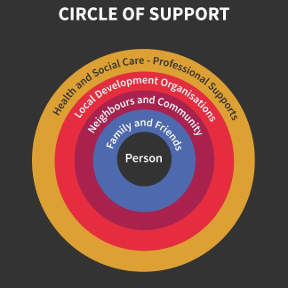

Circles of Psychosocial Support https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/health-assessment/0/steps/42765

Lastly, I would highly recommend sending employees to Psychological First Aid courses. Within a day, trainees would be able to identify and respond to common distress signs and link affected individuals to access further support- mental health helplines, calm circles, therapy etc. Emergency response strategies can then be further developed to include contingency plans to handle mental health crises such as panic attacks and aggression in the workplace safely. In addition, trained employees can double up as first responders who can help fellow colleagues or clients going through distress.

In today’s fast-paced world, organisations are often pressed to remain relevant by maximising profits and putting business needs first. However, organisational cultures can strongly influence employee wellbeing and even indirectly improve profit margins. When we take even the smallest steps towards psychologically safe workplaces that prioritise mental health, we are not just contributing to our internal ESG (environmental, social governance) goals but also creating a safer and more inclusive society for all.

Links for Reference:

Psychological First Aid- https://redcross.sg/get-trained/psychosocial-support.html